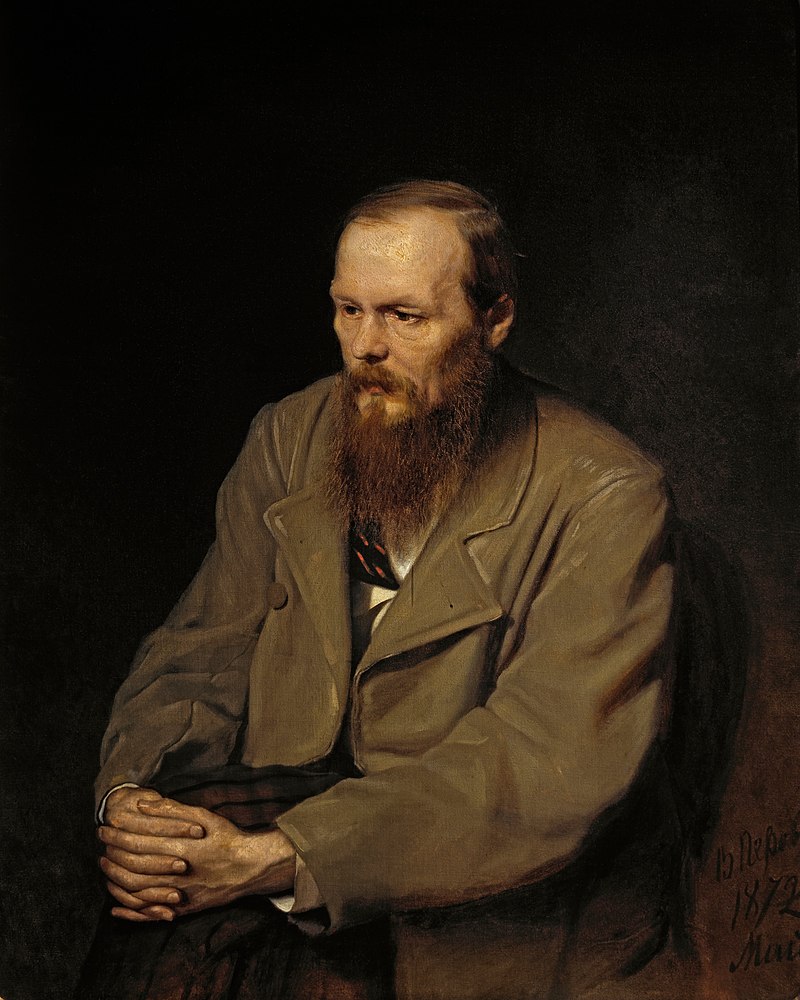

Author: Azur Ekić

When I mention the word ”enlightened” – what image comes to your mind? What kind of a person appears as a visual representation? If it is a common interpretation, an image of an Indian guru, avatar, or some yogi sitting in a lotus position, drunk with ecstasy, perhaps a wise old man with a long beard, then your understanding of enlightenment is still ”mainstream” and superficial. However, enlightenment is not something reserved just for monks and mystics; it occurs with deep thinkers as well, artists, philosophers, even scientists. Some of them do not even realize that they have reached enlightenment, because they do not think in terms of energy, they do not meditate and talk to deities or any form of a spirit guide, they simply lead a pure, selfless life and create such works that benefit humanity. This is the main criterion for enlightenment; after all, it is not meditation, it is a deep devotion to some humane idea. Once you understand this, it should come as no surprise that some famous writers of the past were, in fact, enlightened. During one of his seminars, the para-enlightened Master Ljubiša Stojanović revealed to the people in attendance that most of the Russian romantic writers (Dostojevski, Tolstoy, etc.) were, in fact, enlightened. How this came to be is a mystery, because, from my experience studying these things, when there is not just one individual, but rather – a group of people from a certain region that gets enlightened within the same era, this is usually due to some divine plan, the actions of an avatar, certain energy fields, and so on. An individual getting enlightened is one thing, but when it is an entire group belonging to the same branch, same region, and era, it represents a curious rarity. In this article, we shall explore this claim given by the cosmic energies. And among these enlightened literary giants, few shine as deeply and mysteriously as Fyodor Dostoevsky.

When one hears the name Fyodor Dostoevsky, the mind often recalls a tormented genius, an epileptic visionary, or a master of psychological depth. But according to the understanding of Ljubiša Stojanović, a spiritual teacher whose insights go beyond conventional historiography, Dostoevsky was something far more profound: a spiritually enlightened being. Such a claim may seem lofty—especially in the world of literary criticism—but when viewed through the lens of inner transformation, karmic understanding, and transcendent beauty, Dostoevsky’s life and work offer surprising alignment with the qualities of one who has touched the divine.

The Alchemy of Suffering

To understand Dostoevsky’s spiritual depth, one must first examine the crucible in which it was forged. At age 28, Dostoevsky stood before a firing squad, condemned to death for his involvement in a progressive intellectual circle. Moments before his execution, a royal pardon arrived. What followed was four years of hard labor in a Siberian prison, followed by six more years of forced military service. These experiences crushed the young intellectual arrogance that once animated him and replaced it with a reverent confrontation with suffering, faith, and the soul.

This near-death experience—followed by prolonged exposure to pain, injustice, and moral degradation—did not break him. Instead, it appeared to initiate a spiritual transmutation. He would later write: “Man only likes to count his troubles; he doesn’t calculate his happiness.” Such a statement reveals a consciousness that has begun to detach from the conditioned mind and observe the workings of human suffering with lucidity and compassion.

Beauty as a Transcendent Force

One of Dostoevsky’s most famous and often misunderstood quotes is: “Beauty will save the world.” This line, from The Idiot, is not a superficial aesthetic proclamation. It points to a metaphysical reality: that beauty—true, spiritual beauty—is a reflection of the divine.

In The Idiot, Prince Myshkin is a vessel of unconditional love, innocence, and purity. He is mocked, rejected, and misunderstood, much like Christ himself. Myshkin’s appreciation for beauty is not limited to faces or art; it is a recognition of the sacred spark within the broken and the fallen. In one moment, he says of a woman viewed by society as “fallen”: “She has suffered so much… she is beautiful because she has suffered.”

This perspective transcends moral judgment and moves into the domain of higher seeing—a direct perception of the soul beneath the surface. Myshkin does not analyze; he radiates understanding. Dostoevsky, through him, seems to be saying: Beauty is not appearance, it is essence—and it is the essence of God within man.

The Karmic Design of “Crime and Punishment”

Crime and Punishment, another of Dostoevsky’s masterpieces, offers what can only be described as a karmic parable. Raskolnikov, a proud and desperate man, believes himself justified in murdering a pawnbroker for the sake of a higher cause. Yet from the moment of the act, he is consumed not just by guilt, but by existential collapse.

Rather than being punished externally, Raskolnikov is torn apart from within. His punishment is not legal—it is metaphysical. He becomes ill, paranoid, and emotionally shattered. He cannot escape the energetic consequence of his action. Only when he opens himself to love and humility—through the quiet and luminous presence of Sonia—does redemption begin. This mirrors the karmic path: cause, consequence, collapse, and eventual surrender.

Dostoevsky is not moralizing here. He is revealing the structure of spiritual law. His characters don’t merely suffer; they are purified. They are not condemned; they are transfigured. Through inner torment, they approach the edge of their ego, and only then does light begin to enter.

Faith Through Doubt, Light Through Shadow

Unlike dogmatic religiosity, Dostoevsky’s relationship with the divine is complex, turbulent, and honest. He does not preach—he wrestles. In The Brothers Karamazov, perhaps his most theologically layered novel, he allows Ivan to pose the most searing questions about human suffering and divine justice. But Dostoevsky does not resolve these with argument—he answers through the presence of the saintly Alyosha, a young monk who exudes a subtle, wordless power.

This juxtaposition is key: intellectual doubt is not denied, but transcended. Dostoevsky seems to suggest that the mind cannot grasp God—but the heart can embody Him.

He once wrote: “If someone proved to me that Christ is outside the truth, and that the truth really excluded Christ, I would prefer to remain with Christ rather than with the truth.”

This is not fanaticism—it is mystical prioritization. Truth is no longer an abstraction to him. Truth is alive, and it wears the face of love.

Signs of the Inner Knowing

The enlightened being is not necessarily one who avoids darkness, but one who has passed through it and emerged with light. Dostoevsky’s works reflect this journey. He does not construct morality plays—he descends into the soul’s battlefield. He brings readers face to face with the abyss, only to reveal a hidden bridge across it: humility, forgiveness, and love.

Even his epilepsy, often seen as a purely medical affliction, is worth reexamining. Dostoevsky described moments of seizure as preludes to a kind of bliss—a sacred stillness that no earthly pleasure could match. “I felt that heaven came down to earth and swallowed me,” he once confessed. These are not the words of a man merely sick, but of a consciousness glimpsing beyond the veil.

Conclusion: The Light Beneath the Word

To call Dostoevsky enlightened is not to canonize him in religious terms, but to recognize the unmistakable fragrance of higher perception that runs through his life and work. He saw the soul in its suffering. He saw God in man’s darkest hour. He understood beauty as a redeeming force, suffering as purification, and love as salvation. He did not merely write books—he transmitted a vision.

In a world often seduced by surface and noise, Dostoevsky remains a prophet of the inner world—a reminder that it is not intellect but heart, not opinion but surrender, that reveals the truth.

Perhaps, then, Ljubiša Stojanović was not offering a poetic metaphor, but a diagnosis of spiritual reality. Dostoevsky, in the garments of a 19th-century novelist, may well have been one of the hidden ones—those who walked the earth bearing light cloaked in human drama.