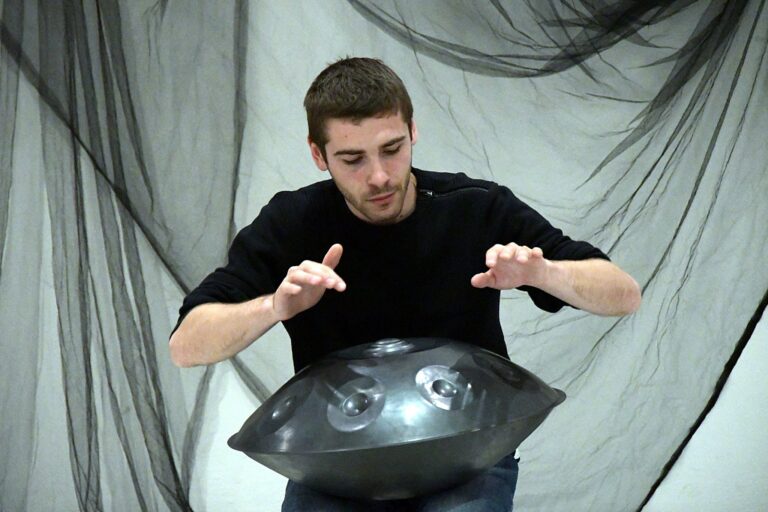

A Handpan Story

Photo: Ognjen Karabegović

An interview with a handpan musician whose melodies enchanted all of us who were privileged to hear it live

The Awakening Times (TAT): How did you get into music, and especially the handpan? When did you first hear about it and fall in love with it?

IVAN JUDAS (IJ): I’ve been into music since I was a kid; I always loved making my own stuff. My parents weren’t really pushing me or anything. I started with the guitar, inspired by my brother, but I gave up after about six months. But we had a piano and other instruments at home, so I was always around music.

As I started messing around with music more and exploring different things, I had a good friend, Iris Tarbuk, who really helped me out. A lot of things just kind of happened…almost “fatefully”. One day I was on YouTube and saw a handpan. I was playing guitar a little then, and I thought the handpan looked really cool, but it was impossible to get one. They cost €3,000, and you had to pay upfront, and I was only 16 or 17 years old at the time.

I realized it wasn’t going to happen, so I started playing djembe—you know, the African drum.

I liked the idea that if I had that instrument, I could just play on the street. Not really for the money, but I knew I could make some…you know…make a living. It seemed like a good way to get out of everything. But back then, it seemed impossible. Who’s going to give a 16-year-old €3,000 for THAT? Everyone would have thought I was crazy.

TAT: Had you played on the street before? Maybe with the guitar or djembe?

IJ: I think I first played on the street when I was about 18 or 19. But I mostly just played at home. The djembe’s really loud, and it felt kind of weird playing it by myself on the street. I figured I’d just be making a lot of noise and bothering people.

TAT: So how did you finally get your first handpan?

IJ: I was in a band called Balkalar, and my friend Irma connected me with Antonio, who had somehow managed to get a handpan from this Italian maker, Shaktipan. There was a six-month waiting list just to get one. I tried playing his handpan, and I just fell in love with it. I really wanted one, but I knew I couldn’t get it, so I just kind of gave up on the idea. I thought, maybe someday. But I at least wanted to meet other people who played it, learn more about it.

That day I went home and added a ton of handpan players on Facebook. The next day, someone invited me to this page called Hoplompan. They were selling two handpans, one for €600 and the other, which was in better shape, for €1,000. I messaged them, and they said they’d hold it for a week. I was 20 at the time, and I asked my mom to lend me the money. I told her I was going to Italy in a week and needed €1,000—or a little less, since I had some money saved up. I even told her I’d go to a loan shark if I had to! I was serious, because I knew I could buy the instrument and make the money back playing on the street. There was a bit of drama, of course, but she realized I wasn’t kidding and gave me the loan. I went to Italy, bought the handpan, and by the end of the summer, I’d paid her back from playing on the street, but she wouldn’t take the money—she said it was a gift.

TAT: We’re interested in the therapeutic side of things. What have your experiences been like with people, and how did you get into what you could call…a certain kind of activism? How did people react, and how did it help them?

IJ: It all happened pretty naturally. I always tell people, I’m not a trained therapist or anything. I don’t see myself as a therapist in that sense, but everyone’s always telling me I’m good at it. It started with playing on the street. Kids would come up, and their parents would ask if they could try it, so I’d show them how. After doing that a lot, I got pretty good at explaining how to play.

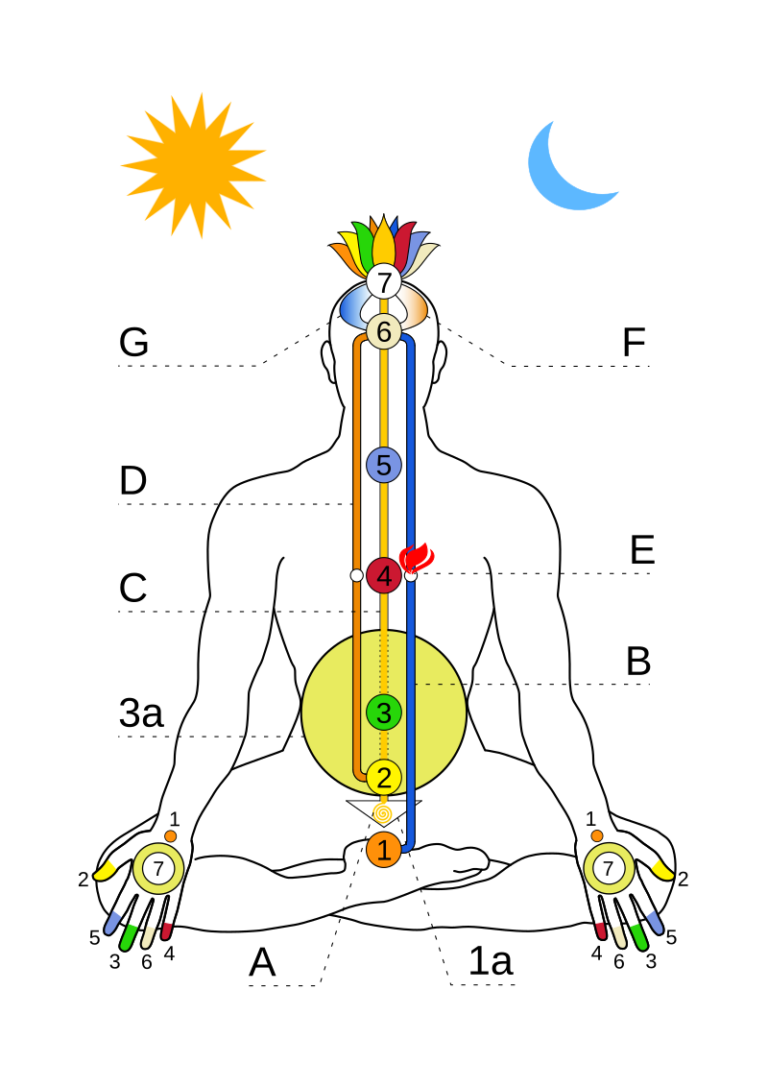

While I was playing on the street, there were all these different interactions, almost like on an energy level—it’s hard to explain. People had really positive reactions, and I felt something inside.

I was also interested in making music for meditation with the handpan. I hadn’t seen anyone doing that around here. I ended up at the Tuškanac Youth Center, playing for kids with special needs.

TAT: How did you end up there?

IJ: Through a woman I’d worked with before. She connected me with them and asked if I wanted to go, and I said yes. I don’t remember exactly how it happened, but it was all pretty spontaneous.

I went there and did a workshop. We didn’t really know what to expect. There was an autistic girl, a deaf girl, and some other kids with different kinds of developmental challenges.

They loved it, they were really happy, and they asked if I wanted to work there, but I would have had to get some kind of therapy training. I said I could come as a guest, but I didn’t really see myself as a therapist long-term. I just wanted to play music.

When I played, people would say their headaches or other pains went away. Some people even had these really intense experiences, almost like shamanic journeys.

TAT: What’s the strangest thing that’s happened?

IJ: Some people have had visions, and some have felt like they went on a shamanic trip. I never really defined it. I just told them it was relaxing music and watched what happened. When people ask me what I do, I say, “I play music from the heart.” I go inside myself, to my heart, and do what I love. I just put that out there. That’s my love.

What people get from it is up to them. I give what I love, but what they feel is different for everyone. I don’t like to share other people’s stories because I don’t want to give anyone any ideas about what they should feel. I want everyone to have their own experience and then tell me about it, without any expectations.

Also, it’s still a pretty new instrument for a lot of people, which makes it even more interesting, especially when I’m playing on the street.

I’m working with an autistic guy right now.

TAT: Is it helping him?

IJ: We’re still trying to figure that out. It’s a process, so I can’t say for sure. I don’t want to jump to conclusions based on how I feel about it.

The first time I met an autistic person was totally random. I was playing on the street in Pula. I was going through a tough time, some personal stuff, and I was playing to clear my head, to feel more independent. Money wasn’t the main thing… but I was wondering if any of this was worth it in the long run.

TAT: A lot of artists have that same problem…

IJ: Yeah. And that day, I was feeling really down, playing on the street… and this little girl comes up and starts asking me about the instrument. She tries playing it, and then her mom comes over with her other daughter, her sister. The mom’s just staring at me, crying. I didn’t know what was going on. I thought she was just happy her kid was playing. I asked if her other daughter wanted to try, and the mom said, “No, no, it’s her I’m worried about.”

It turned out the girl was autistic. And her mom said, “This is the first time she’s ever gone up to anyone, especially a stranger. It’s amazing.” She even wanted to buy a handpan right then and there.

I helped them find one. She started playing. I lost touch with them after that, but a year or two later, I saw a video of her playing the handpan at a school thing, even playing a melody I’d taught her, or at least something like it.

TAT: Wait, so this autistic girl started playing after meeting you?

IJ: Yeah. But I didn’t hear from them again after that.

TAT: You were having doubts about what you were doing… That must have been a huge boost, seeing an autistic kid playing because of you.

IJ: Totally, it was like an answer. I was feeling terrible, really down, wondering what the point of all this was. Not because of the money, but just… doubts. But then I saw that, and I realized it does have a point! It’s way more powerful than I thought. It was a real “wow” moment. I couldn’t really explain it to other people, because they were still skeptical about what I was doing. I was really proud of myself. And happy that I could give that to someone.

And there have been a lot of other experiences like that, not just with autistic kids, but with all kinds of people.

In Čakovec, I applied to play at some events. I just Googled different organizations and told them, “I’m out of work, I need to get myself out there.” I thought, even if I’m not doing anything else, I’d like to at least do some good deeds.

I’m going to have a chance to play for older people for the first time soon, too.

It’s just amazing.

I offered to play for free, as a volunteer, for all these different groups. I played for kids with cerebral palsy a few times. That was an amazing experience. The first time, they couldn’t really play, but I still managed to connect with them. Like, if I just held their hand, everything was fine, but when they tried to hit the handpan, they’d just freeze up. Even if I just touched their hand, there was so much resistance, it was almost like a superhuman force pushing back! I don’t know a lot about cerebral palsy, but I’d never felt resistance like that. But I tried to connect with them emotionally. I’d tell them to imagine a river, a stream, pebbles… visual stuff, trying to help them relax. It kind of worked, but not enough to really make a difference.

But I realized something I already knew, but didn’t realize how deep it went: how much someone’s emotions are connected to their physical state. I’d tell them, “You have to relax to play,” but nothing would happen. But when I said, “You can’t be relaxed to play,” they’d suddenly start playing. It was like reverse psychology. I mess around with people like that a lot, trying different things. It’s trial and error—it either works or it doesn’t, but I just try not to hurt anyone’s feelings. And it worked! I asked one girl, “How does it feel now that you did it?” She just looked at me, didn’t say anything, but I felt this incredible warmth… I don’t know if it was her feeling or mine, but it was amazing. And the other kids in the group started playing better too.

The second time I went, some of them were already playing, getting some sounds out. Before, they were so tense. So something definitely helped. I don’t know why they haven’t called me back; I need to get in touch with them again. It was a really interesting experience. I even used that same trick with another person. I told her to relax, and she tensed up, so I tried saying, “Don’t be relaxed,” and she just started playing. *laughs*

TAT: So it’s like the blockage is connected to a feeling of being told not to do something?

IJ: Yeah, almost like they’re being defiant, but I don’t know why.

Those are things I need to look into more. I’ve noticed some things that seem to work in general. I didn’t treat them like they were sick or anything; I treated them like anyone else. Of course, it was harder; I didn’t know if they’d be able to do it. I’d think, “This is pointless, why am I even here?” But you have to try to see things from their perspective. Even if someone manages to make one sound with the handpan, it could mean the world to them. One girl who barely got a sound out was so happy; she loved the feeling, that one sound, that vibration, it was amazing for her.

One person said, “This isn’t for me, I don’t like it,” and that’s fine. One didn’t even want to try, even though the others were trying to get him to. But the others were saying, “This is really relaxing, you have to try it!”

But all of them in the group saying it relaxed them… again, I can’t talk about any long-term effects.

TAT: You’re not a trained therapist, but you’ve kind of developed a therapeutic approach through working with people. You’ve had to learn how to work with all these different people and learn those skills, through experience, learning how to adapt your communication, and so on…

IJ: Yeah, but like I said, I’m not a therapist, and I can’t say anything for sure. I just learn by doing it, watching people, seeing what happens, noticing patterns. But that was never the plan; it just happened.

There’s this story about a psychiatrist who has patients, and the way he helps them is by working through their problems himself, making changes within himself to help them heal. There’s a book about it, I haven’t read it, but the story’s interesting. That’s kind of how it feels. I’m there, I’m present, and when someone starts playing, I feel things, even if I don’t know exactly what they’re feeling. I feel this tension, and then I breathe through it and relax, and then they start playing. Sometimes it’s verbal, sometimes it’s not. But I try to connect with everyone in their own way. I want to give everyone the attention they deserve. Sometimes people uncover past traumas. It could be from bad experiences in music school. People start playing and just hit a wall.

For example, I’ll see someone who’s really tense and holding back anger. I’ll ask them what’s wrong. I even told one person, “Just tell everyone to go to hell!” We even yelled it together, and that released all that emotion. They were suddenly happy, like a weight had been lifted, and they finally said it without anyone judging them. Even though they were swearing, it was okay, and then… they started playing! They let it go, laughed, and that was the key.

And today, at the festival, I asked a girl, “What’s your favorite thing to do in life? Think about that.” Once I’ve brought something like that up, I don’t push it. If they’ve already realized something, I don’t repeat it.

TAT: Personally, I thought I wouldn’t be able to do it because I don’t have good fine motor skills, but then with your help I did string together a few notes.

IJ: Yeah, a lot of people think that, but it’s all in your head. It just takes practice. Your brain is like a computer; you can learn anything with experience and practice.

TAT: That’s a good message for readers. With training and practice, you can learn things that seem really hard.

IJ: Yeah. Right now, I’m working with a woman named Gordana and her son, Stjepan. He’s autistic. This is the first time I’ve had the chance to work with someone autistic consistently over a longer period, so I’ll be able to learn a lot more.

TAT: Are there any plans to work with therapists, do some research, document all this?

IJ: My dad’s a neuroscientist, he’s a vice-rector at a university, and Gordana’s worked with people on similar stuff before, and she’s trying to get that going again. What we’re doing could maybe get some attention, but we need to see some results first before scientists will be interested. There’s not really any funding for this kind of research here in this country, so for now, I’m just doing all of this on my own time and money.

It’s already pretty tough, because I’m trying to make a living for me and my girlfriend, but I believe that if I’m doing something I love, things will work out. And they have been; doors are opening.

We’ve noticed a lot of things already, and his mom is really interested and has definitely noticed some changes, that’s the reason she called me and chose me. I’m definitely curious; I mean, I don’t see how this could hurt anyone, so why not give them the chance to experience music? I’m just curious what’s possible to achieve with music.

TAT: Do you have a YouTube channel where people can listen to your music?