Author: S. A. Rao-Rane, Research Fellow & Yoga Therapist

A Conceptual History of Psychology charts the development of psychology from its foundations in ancient philosophy to the dynamic scientific field it is today. Psychology is the study of the human mind, and is the basis for many forms of mental health treatment, particularly psychotherapy. Psychology plays a role in our behaviors, emotions, relationships, personality, and much more.The mind is the part of a person that thinks, feels, perceives, remembers, and wills. It includes both conscious and unconscious processes. The mind is closely linked to the brain, but the exact nature of the mind is disputed.

The mind enables a person to be aware of both their internal and external circumstances, influencing their thoughts, emotions, and actions. It plays a central role in nearly every aspect of human life. While the mind and brain are closely related, they are distinct: the brain is a physical organ composed of nerve cells that coordinates movements, feelings, and bodily functions, whereas the mind is a mental faculty that cannot be physically touched. Different philosophical views attempt to explain the mind. Functionalists believe that the mind is what the brain does, while identity theorists claim that the mind is the brain. Some characterizations focus on the internal workings of the mind, emphasizing its role in transforming information. Related concepts include consciousness, which refers to the experiential aspects of the mind, and the unconscious, a part of the mind that can influence a person without their awareness or intention.

In Vedanta philosophy, the mind is a subtle substance that is made up of three gunas or modifications of matter. The mind is also considered to be an internal organ.

In Vedantic philosophy, the mind and its qualities are explained through the concept of the three gunas: Sattva, which represents knowledge and calmness; Rajas, which represents activity and desire; and Tamas, which signifies laziness and ignorance. The mind serves several essential functions—it is responsible for decision-making, conceit, recollection, and perception, and it is said to be permeated throughout the body of the Jiva (the individual soul). One of the key capacities of the mind is purification, which involves the betterment of character. This can be achieved in various ways: by consuming wholesome food, by cultivating a mental constitution in which sattva dominates over rajas and tamas, and by making a firm commitment to follow moral conduct. The consciousness of the mind is ultimately due to the presence of the Atman, the true Self, which is distinct from both mind and matter.

The mind and matter are different grades of the same material substratum

The grossest part turns into excrement, the medium constituent becomes the flesh and the subtlest part forms the mind. According to Advaita Vedanta, the mind is compound of three substantive forces called gunas, namely, sattva, rajas and tamas, which are also the basic constituents for the entire universe

Mind and Its Purification in the Philosophy of Advaita Vedanta

The concept of mind occupies an important place in the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta. The mind consists of three gunas, namely, sattva, rajas and tamas. Every man is a combination of all the three gunas, in varying proportions and they constantly act on one another. Sattva represents knowledge and calmness, Rajas represents activity and desire, and Tamas represents laziness and ignorance. The mind is capable of purification (citta suddhi/ sattva suddhi). It refers to the betterment of character. Purification of the mind is the mandatory condition for the onset of Brahman-atman knowledge. Purification of the mind is effected by providing the mind with wholesome food and through the process of bringing about a change in the constitution of the mind in such a manner that sattva predominates over the other two gunas, namely rajas and tamas.

THE MIND, ACCORDING TO ADVAITA VEDANTA

The conception of the mind (also known as antaHkaraNam) varies in the different systems of Indian philosophy, as stated below.

The mind, being made of extremely subtle and transparent substance, receives the reflection of the consciousness of the Self. Because of this, it appears to be sentient, though it is really inert. All knowledge arises only through an appropriate modification of the mind, corresponding to the object of knowledge.

In his bhAshya on gItA, 6.19, Shri Shankara says: A lamp does not flicker when it is in a windless place. Such a lamp is compared to the mind of a yogi whose mind is under control when he is engaged in concentration on the Self.

Panchadashi, 2.13 says that it is the mind that examines the merits and defects of the objects perceived through the senses. The conclusion which the mind comes to will depend on the proportion of the three guNas in it at the time.

From the above two quotations it is seen that the mind remains dormant in deep sleep, but in concentration on the Self the mind becomes identified with brahman.

The nyAya-vaisheShika system considers the mind to be an eternal substance, atomic in size. The prAbhAkara school of pUrva mImAmsA holds the same view. The bhATTa school of pUrva mImAmsA maintains that the mind is all-pervasive and is in eternal contact with the allpervasive Atman; that Atman and mind, in contact with each other, function only within the sphere of the body with which they happen to be associated; and the possibility of several cognitions arising at the same time cannot be ruled out. The sAnkhyA and yoga systems consider the mind to be of the size of the body.

According to Advaita Vedanta the mind is a subtle substance (dravya). It is neither atomic nor infinite in size, but it is said to be of madhyama pariNAma, medium size, which may be taken to mean that it pervades the body of the particular jIva to which it belongs. The mind of each jIva is different. It has a beginning, as is proved by such shruti statements as, “It (Brahman) projected the mind” (br. up. 1.2.1). (VedAnta paribhASha).

In mANdUkya kArika, III. 35 it is said:– The mind loses itself in sleep, but does not lose itself when under control. That very mind becomes the fearless brahman, possessed of the light of consciousness all around. In his bhAshya on mANDUkya kArika, III. 46 Sri Sankara says:– When the mind becomes motionless, like a lamp in a windless place, it does not appear in the form of any object imagined outside; when the mind assumes such characteristics, then it becomes brahman; or in other words, the mind then becomes identified with brahman.

The mind, which is called ‘internal organ’ (antaHkaraNam), is produced from the sattva part of all the five subtle elements together. It is known by four different names according to the function. The four names aremanas, buddhi, chittam and ahamkAra. (Sometimes only two names, manas and buddhi, are mentioned, as in Panchadashi.1.20, the other two being included in them). The function of cogitation is known as the manas or mind. When a determination is made, it is known as buddhi or intellect. The function of storing experiences in memory is called chittam . Egoism is ahamkAra. The word ‘mind’ is also used to denote the antaHkaraNam as a whole when these distinctions are not intended.

According to one theory, known as the prasankhyAna theory, attributed to MaNDana Mishra, the knowledge which arises from the mahAvAkya is relational and mediate, like any other knowledge arising from a sentence.

The mahAvAkya gives rise to Self-knowledge by making the mind take the ‘form’ of brahman. This is known as akhaNDAkAra vRitti. The question arises– since brahman has no form, what is meant by saying that the mind takes the form of brahman? This is explained by SvAmi VidyAraNya in Jivanmuktiviveka, chapter 3 by taking an example. (In the first place, the word ‘AkAra’ in these contexts should be taken as meaning ‘nature’.

Such a knowledge cannot apprehend brahman which is non-relational and immediate (aparoksha). Meditation (prasankhyAna) gives rise to another knowledge which is non-relational and immediate. It is this knowledge that destroys nescience. In this view the mind plays an important role in the production of Self-knowledge.

the mind, in the act of being born, comes into existence full of the consciousness of the Self. It takes on, after its birth, due to the influence of virtue and vice, the form of pots, cloths, colour, taste, pleasure, pain, and other transformations, just like melted copper cast into moulds. Of these, the transformations such as colour, taste and the like, which are not-Self, can be removed from the mind, but the form of the Self, which does not depend on any external cause, cannot be removed at all. Thus, when all other ideas are removed from the mind, the Self is realized without any impediment. It has been said-“One should cause the mind which, by its very nature, is ever prone to assume either of the two forms of the Self and the not-Self, to throw into the background the perception of the not-Self, by taking on the form of the Self alone”. And also—“The mind takes on the form of pleasure, pain and the like, because of the influence of virtue and vice, whereas the form of the mind, in its native aspect, is not conditioned by any extraneous cause.—“The mind takes on the form of pleasure, pain and the like, because of the influence of virtue and vice, whereas the form of the mind, in its native aspect, is not conditioned by any extraneous cause. To the mind devoid of all transformations is revealed the supreme Bliss”. Thus, when the mind is emptied of all other thoughts Selfknowledge arises.

Chandogya upanishad, 6. 5. 1 says: “The food that is eaten becomes divided into three parts. The grossest part becomes excreta. The medium constituent becomes flesh. The subtlest part becomes mind (antaHkaraNam)”.

In his bhAshya on this mantra Shri Shankara says: “Getting transformed into the mind-stuff, the subtlest part of the food nourishes the mind. Since the mind is nourished by food, it is certainly made of matter. But it is not considered to be eternal and partless as held by the vaisheShikas”.

The mind is the cause of happiness and unhappiness. A person is happy when other living beings or inanimate objects are favourable to him, and unhappy when they are unfavourable. A thing or person is considered favourable when that thing or person responds in the way desired. If a son obeys his father, the father is happy; if he does not, the father is unhappy. A person is happy with his car or any other object as long as it functions well; if it does not, he is unhappy and wants to get rid of it. It is thus clear that happiness and unhappiness are only states of the mind, but are wrongly thought to be caused by external objects. Happiness is the result of the mind becoming calm. The mind becomes calm temporarily when a particular desire is fulfilled, and then happiness is experienced. But soon another desire crops up and agitates the mind, causing unhappiness. Thus it is clear that lasting happiness cannot be attained by the fulfillment of desires.

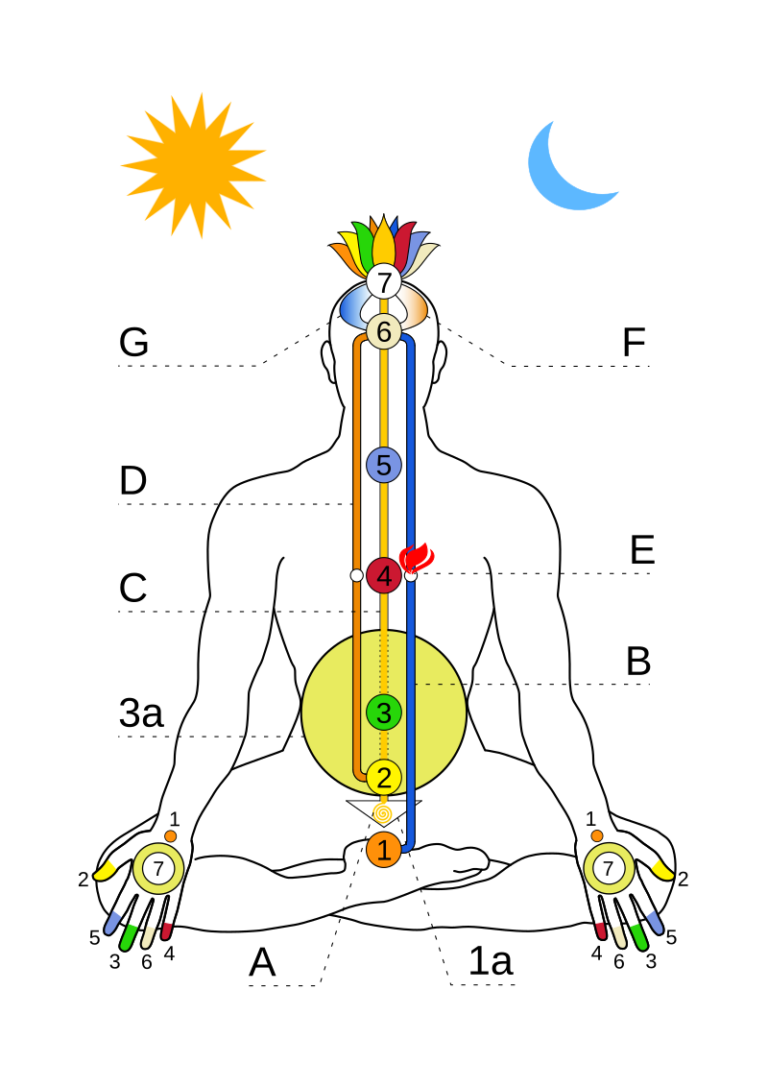

In the Taittirıya Upanisad 2.7, an individual is represented in terms of five different sheaths or levels that enclose the individual’s self (Figure 3). These levels, shown in an ascending order, are:

• The physical body (annamaya kosa)

• Energy sheath (pranamaya kosa)

• Mental sheath (manomaya kosa)

• Intellect sheath (vijnanamaya kosa)

• Bliss sheath (anandamaya kosa)

These sheaths are defined at increasingly finer levels. At the highest level is the Self. It is significant that ananda is placed higher than the intellect. This is a recognition of the fact that eventually meaning is communicated by associations which are extra-logical.

The energy that underlies physical and mental processes is prana. One may look at an individual at three different levels. At the lowest level is the physical body, at the next higher level is the energy system at work, and at the next higher level are the thoughts. Since the three levels are interrelated, the energy situation may be changed by inputs either at the physical level or at the mental level. When the energy state is agitated and restless, it is characterised by rajas; when it is dull and lethargic, it is characterised by tamas. The state of equilibrium and balance is termed sattva.

Prana, or energy, is described as the currency, or the medium of exchange, of the psychophysiological system. The higher three levels are often lumped together and called the mind.

Detachment is the key to lasting happiness. True and lasting happiness can result only if the mind is permanently kept calm. This can be achieved only if desires, which are the cause of mental agitation, are completely eliminated. We are therefore led to the conclusion that total detachment towards all worldly pleasures (Vairagya) is the only means for the attainment of true and lasting happiness, which is brahmAnanda.

Vairagya is the most essential requisite for a person who wishes to attain Self-knowledge, which alone will lead to eternal bliss. It is said in vivekachUDAmaNi that one who attempts to attain Self-knowledge without cultivating dispassion is like a person trying to cross a river on the back of a crocodile, mistaking it for a floating log of wood. He is sure to be eaten up by the crocodile midway.

The purification of the mind (citta suddhi/sattva suddhi) According to Advaita Vedanta, the mind is capable of purification (citta suddhi/ sattva suddhi). It refers to the betterment of character.

According to Advaita Vedanta, purification of the mind is effected by providing the mind with wholesome food and through the process of bringing about a change in the constitution of the mind in such a manner that sattva predominates over the other two gunas, namely rajas and tamas.

The Bhagavad Gita (Chapter XIV, Verse 18) proclaims that the inner journey of mind purification starts from a predominantly tamasic state of existence to the rajasic state, and in turn, from a predominantly rajasic state of existence to the sattvic state of existence. Thus, we are able to observe that the mind is capable of purification and a purified mind enable the realization of the self/Brahman-atman, in the philosophy of Advaita Vedanta.

CONCLUSION

From the foregone discussion, we are able to observe the fact that the concept of mind is an important cog in the wheel of Advaita Vedanta. It is often stated that the one’s own mind is the cause for bondage as well as for liberation.

Understanding The Vedic Model Of The Mind

The mind may be viewed to be constituted by five basic components: manas, ahamkara, citta, buddhi and atman.

The Vedic theory of consciousness probably suggests a process of evolution, wherein there is an urge to evolve into higher forms, which have a better grasp of the nature of the universe.

A person is compared to a chariot that is pulled in different directions by the horses yoked to it, with the horses representing the senses. The mind is the driver who holds the reins, but next to the mind sits the master of the chariot – the true observer, the self, who represents a universal unity. Without this self no coherent behaviour is possible.

All creatures enjoy only a particle of this bliss (the Bliss that is the very nature of brahman). We wrongly think that happiness comes from external objects. All the happiness that we enjoy is only a reflection of brahmAnanda in the mind when the mind is calm.

The Bhagavad Gita (Chapter VI. Verse 5) proclaims that one must oneself subdue one’s weakness and raise oneself by oneself. Let us conclude by understanding that Advaita Vedanta is very positive and practical in showing that whatever be the present state of a man’s mind, the mind can always be purified for the onset of Brahman-atman knowledge/ realization. Further, we are also able to understand that the purification of the mind may be effected irrespective of caste, creed, culture, religion, class, gender, etc. This reflects the all-inclusive and universal nature of Advaita Vedanta.

Universal Categories

If the categories of the mind are taken to arise from the recognition of shadow mental images, then how are these categories associated with a single “agent”, and how does the mind bootstrap these shadow categories to find the nature of reality?

Answers to these questions were developed within the frameworks of Vaisnavism as well as Saivism.

For example, the twenty-five categories of Samkhya form the substratum of the classification in Saivism. Samkhya assumes that non-material entities have their own existence.

The material elements (bhuta) are represented by earth, water, fire, air and ether. Paralleling them are five subtle elements (tanmatra), represented by smell, taste, form, touch and sound; five organs of action (karmendriya), represented by reproduction, excretion, locomotion, grasping and speech; five organs of cognition (jnanendriya), related to smell, taste, vision, touch and hearing; the inner instrument (antahkarana) being mind, ego and intellect; inherent nature (prakrti); and consciousness (purusa).

These categories define the structure of the physical world and of conscious agents and their minds. Saivism enumerates further categories related to consciousness, but we shall not speak of them here.

The Vedic theory of consciousness may also be taken to suggest a process of evolution. In this evolutionary model, the higher animals have a greater capacity to grasp the nature of the universe. The urge to evolve into higher forms is taken to be inherent in nature. A system of an evolution from inanimate to progressively higher life is clearly spelt out in the system of Samkhya. At the mythological level, this is represented by an ascent of Visnu through the forms of fish, tortoise, boar, man-lion, the dwarf into man.

A Vaisnava enlargement of the Vedic theory of the mind is provided by the Pancaratra tradition. Here Vasudeva or Krsna represent the ground-stuff of reality. Vasudeva is also called ksetrajna, the knower of the field.

Concluding Remarks

Let us return to mainstream science. Quantum mechanics has thrown up a multitude of paradoxes that cannot be understood in the framework of reductionist physics. For example, we have nonlocal effects that can propagate instantaneously over enormous distances. Another famous example is the Wheeler delayed-choice experiment, according to which our decisions now can alter the remote past. These effects establish that the idea of an objective reality, visualised in terms of material objects, is invalid. What we need is a theory that incorporates the subjective and the objective in a comprehensive whole. Current research suggests that such a theory will be based fundamentally on quantum physics, but it will go beyond it in its comprehensiveness.

Vaisnava metaphysics confronts the question of objective and subjective reality directly. It presents its resolution in terms of a paradoxical unity between consciousness and the material world. The details of the cognitive structure, which may be termed Vaisnava Tantra, belong to esoteric traditions and are not well known in the academic world. Let it also be said that Saiva metaphysics is similar to Vaisnava metaphysics, although there are some differences in emphasis. Saiva Tantra, likewise, has parallels with Vaisnava Tantra. The image of Harihara symbolises this identity.

An important corollary of the notion that consciousness has an existence of its own is that creativity need not be a result of only “mechanical” thought. Artists and scientists speak of flashes of intuition where, mysteriously, without conscious thought a previous problem is surmounted. Likewise, students of scientific creativity accept that conceptual advances do not appear in any rational manner. Might not then one accept the claim of the great, self-taught mathematician, Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920), that his theorems were revealed to him in his dreams by the goddess Namagiri? This claim, so persistently made by Ramanujan, has generally been dismissed by his biographers. Were Ramanujan’s astonishing discoveries instrumented by the autonomously creative potential of consciousness represented to him by the image of Namagiri? If that be the case, then the marvellous imagination shown in the Yoga-Vasistha and other Indian texts becomes easier to comprehend.

To conclude, the Vaisnava approach to reality is a systematic analysis that distinguishes the domain of the material from that of the agent, who is Vasudeva. It is in complete opposition to the materialist position which regards consciousness as emerging from the material ground. But the materialist position cannot explain how this emergent entity, mysteriously, makes a break in the cycle of cause and effect. Why do we suddenly obtain the sentient from the insentient? On the other hand, the Vaisnava position declares the universe, in the form of Vasudeva, to be sentient and considers the materiality of the ksara purusa to be a part of the divine play (lıla) of Krsna.